- Home

- Beaudoin, Sean

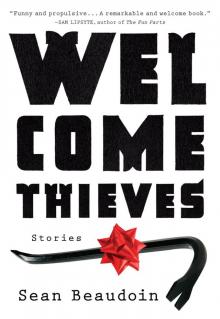

Welcome Thieves

Welcome Thieves Read online

WELCOME

THIEVES

Stories

SEAN BEAUDOIN

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2016

To Cathy, who for fifteen years

has held my hand, heart,

and cliché in equal measure.

The following stories have appeared elsewhere, often in different form. “Nick in Nine (9) Movements” in Litro Magazine. “Hey Monkey Chow” in Bat City Review. “D.C. Metro” in The Nervous Breakdown. “All Dreams Are Night Dreams” in Narrative Magazine. “And Now Let’s Have Some Fun” in Identity Theory. “Tiffany Marzano’s Got a Record” in Redivider. “Comedy Hour” in Another Chicago Magazine. “Exposure” in Instant City. “Welcome Thieves” in Glimmer Train.

Contents

Nick in Nine (9) Movements

The Rescues

Hey Monkey Chow

D.C. Metro

All Dreams Are Night Dreams

You Too Can Graduate in Three Years with a Degree in Contextual Semiotics

And Now Let’s Have Some Fun

Tiffany Marzano’s Got a Record

Comedy Hour

Base Omega Has Twelve Dictates

Exposure

Welcome Thieves

About the Author

About Algonquin

Nick in Nine (9) Movements

Nick becomes Nikki, Duff was always Duff. They start playing in ninth grade because Duff’s stepbrother is in a band called Lewinsky Rescue and sometimes the stepbrother gets laid, so why not? But mostly they drink and wear tube socks and have a van. It’s fun. They come up with a name, Torrentials, and play hardcore, which is not punk and so involves constantly correcting people. Duff says, “Hardcore is to a pickax what punk is to lipstick.”

There are some fights.

Duff wears an earring and a Gibson SG, has natural rhythm and easy chops. Shaves his head. Kicks who needs kicking. Nikki’s too pretty to pretend that everything sucks, but tries. Gets an E-string tattoo, tags deli Dumpsters, parties with that drummer with the infected toe. Still, he’s always a beat behind, a measure off, up in his room running scales every second he’s not being yelled at by the guy who isn’t Dad but moved in anyway.

Some equipment must be acquired.

Duff says they should rip off a dance band. Or cut a hole in the roof of Kane’s Guitars, lower a rope, and haul up Johnny Ramone’s Strat. “Good idea, tier boss,” Nikki says, gets two jobs, quits two jobs, finally snags an off-brand bass on layaway. No label, no logo, made in Seoul. It’s called “Bass.” The plastic case is lined with fake pink fur that Duff says smells like pussy, which makes Nikki think Duff was lying about all those cheerleaders because it smells nothing like pussy and Nikki would know since he’s been hanging out at Dana Goldstein’s for months, especially on Sunday nights when both her parents work and they can listen to Agnostic Front on the futon.

Some glue is sniffed.

Torrentials play their first show, eight bands all ages mosh pits low ceilings. Sharpie Xs and studded belts. Aiming for Fugazi while pretending not to. But it works. The skinheads gob less than usual, say, Eh, yer okay. The girls in leather skirts nod in time to the beat, in time to each other, gaze over Wayfarers at Nikki’s low rumble.

Some gas is huffed.

The next day Duff decides he doesn’t like their name anymore, wants to change to November Regions. Nikki thinks November Regions is the lamest fucking name in the history of lame fucking names.

It sounds like a tampon commercial.

It sounds like a free U2 download.

Which means it’s perfect, since Nikki secretly wants to be huge. Wants to bend over like Green Day, get corporate-label famous, a ruinous admission he covers by pretending to be pissed, punches an amp, cracks two knuckles.

Duff apologizes by spray painting the wall of the practice space JESUS LOVES TORRENTIALS. There’s an anarchy circle around the A. Nikki has zero clue what anarchy is, or even wants to be. Something about wallet chains and waiters getting more per hour, plus tips. The band rounds out. A kid named Drew takes over drums, too good for his own good, runs jazz patterns in the middle of songs. Max Verbal is lead screamer, has a pompadour, brings sixers of Bud Light and refuses to share. He looks sort of like fat Morrissey, which Nikki knows because he stood lookout while Duff five-fingered Meat Is Murder from Record World.

Torrentials have four songs. Three originals, which suck, and a cover of Thompson Twins’s “Hold Me Now,” which sucks. Max Verbal keeps not sharing his beer and going, “Besides, they’re not really even twins.” Nikki transposes half a Doobie Brothers just so Verbal can go, “Besides, they’re not really even brothers.”

They play a couple parties and then a battle of the bands in the school auditorium. After the last song Duff smashes someone else’s guitar.

The audience goes crazy.

The kid holds his broken neck, his snapped strings.

Torrentials get the most votes, don’t win.

There are some fights.

PROM IS FOR SUCKERS, cap and gown for fags. Except hardcore is about inclusivity and subverting exactly the sort of culture that continues to validate such a word. Fine, Duff says, but insists there’s no way he’s wearing a blue smock, even though he failed chemistry and isn’t graduating anyway.

The after-party is lame, so they steal a bottle of wine and climb a tree, take turns reading the first twenty pages of Tropic of Cancer by flashlight.

“We gotta hit Europe, yo,” Duff says, currently working yo and kid into every other sentence. “Which means we gotta get paid, kid.”

They land the same telemarket job downtown, sit across from each other at a folding table full of dial-up phones, give away free passes to a health club. You need to get in shape, yo? You like to push iron, kid? Almost everyone hangs up immediately. Then a girl at the next table figures out how to dial Japan, for a week the whole room calling Tokyo porn lines and asking confused housewives if they’re Yakuza, do they want to win a free pinkie finger?

They quit after the second paycheck, sleep three nights at LaGuardia on standby, get seats on a cargo flight with no seats. Nikki couldn’t cram Bass into his ancient JanSport, so he bought a harmonica. Not very hardcore but easy to hit the three notes that matter. They land in Berlin, follow the same route Von Clausewitz used to subjugate Poland. Or maybe it was the other direction. Duff grows his hair out. Nikki reaches for a mustache. They stand in the middle of squares and the front of cafés, mostly do blues in E since any other key means drowning in that chordy Dylan routine even Dylan only pulls off half the time.

People stop, watch, walk away.

There are some pigeons.

There is some change.

Duff and Nikki become known as Der Witzel-something, which everyone swears is a compliment, but then Klink gets wind and keeps sending Schultz to disperse the crowd. The Euro-hipsters boo, but not too much, since Euro-cops carry machine guns and aren’t shy with the boot. In Hamburg, Duff scores a Gretel who gives them a floor and then a week later a ride north. She’s on her way to some protest, which basically means smoke pot, wear an Arafat scarf, and chant about not building one thing in favor of building another, better thing.

On the streets of Stockholm a guy in a business suit listens for a minute and then yells, “You know nothing about the blues! Go find another hobby!”

Duff wants to follow the dude, get into it.

“It’s bad luck to punch a Swede,” Nikki says, which probably isn’t true, but keeps them from spending July in Stockholm Rikers.

THEY’VE BEEN BACK four months. Duff’s got the clap and three new tattoos. GORE CLUB and PSYCHIC TV and AVAIL. His cousin paints houses on Nantucket, knows a guy who knows a guy. Plus tetracycline. Duff takes

Nikki’s suitcase more than borrows it, grubs twelve bucks in change, ready to hit the road.

There are some hugs.

Nikki fills out three forms, waits, almost throws away the envelope that says he’s won a partial scholarship to a place in Ohio no one has ever heard of. Something State. Dude name of Pell good for a grant. Nikki flags the Greyhound with a Hefty bag full of socks and a well-thumbed Genet. Thirteen hours later a cute girl finally gets on, sits by the window, snores. At school an index card on the message board says CHEAP SAX LESSONS. Nikki buys a 1941 Conn alto for a hundred Pell-bucks and squonks away behind the dorm for weeks before producing a single pure note. It’s fantastic. The sax teacher is called Tumast. No last name. Tumast refuses to come on campus, says, “Too many white girls without bras make me nervous.” Nikki skates over to his place, more a barn than a shack. More one big room with no kitchen than a place you’d be cool going barefoot. Tumast has three enormous gleaming tenors lined against the wall, tries to sell Nikki the dented one.

After a discussion of John Lee Hooker’s mad chops, Tumast nods, says, “You pretty cool for — ”

“A white dude?”

“Was gonna say nineteen.”

They both laugh.

The phone keeps ringing. Tumast takes off his shirt and pulls yards of Saran Wrap around his waist, says the sweat helps “tighten his shit up.” Nikki learns how to play a high C scale, pictures the neighbors as they wince over their frozen dinners, eye their tortured dogs.

Sometimes Tumast scratches at his dandruffy Afro, nods off midsentence.

Nikki figures it’s just been a long day.

CLASSES. THAT DRUNK PROFESSOR. Behind the bleachers while football. The library and everything in it not read. Nikki and a little thing named Chelsea, expensive sweaters and wine-dark skin, crashing through cornfields in her dad’s Miata. Late nights with cough syrup and candles and Nick Cave, “It’s so cool you have the same name,” her wide hips and cheap panties, making eggs while she sleeps it off.

He tries out for a few bands, this one too strummy, that one too singer-songwritery. Then a thrash outfit with inverted crosses and eye makeup, afterward the lead screamer going, “Hey, you’re not half-bad.”

But the dude reminds him too much of Duff.

There is some spoken word.

Someone’s half-finished film.

A short story stolen almost entirely from Ray Carver.

Calling Raymond Carver “Ray.”

A keg and that guy down the hall who spreads his Kawasaki 750 out on the carpet twice a week.

Fall, winter, spring. Fall again.

That year there was always some prick with a didgeridoo.

DUFF ROLLS INTO TOWN unannounced, three blankets and an ’88 LeBaron, moves into the low-slung apartments just off campus everyone calls Crackland. Claims he’s signed up for classes but unless there’s a master’s program in eyeballing eighths, or a PhD in convincing waitresses not to sweat the condom, Nikki doubts it. They jam, Duff slash-fingered and manic, lots of great ideas for liner notes and string arrangements, lots of back slaps and a considered misreading of the circle of fifths.

There are some tantrums.

Duff gets angry when he can’t get his amp to “make that crunchy sound like last time.” At a party with barrel fires outside he makes a cross with duct tape and two sticks to protest church or some shit, tosses it in, realizes too late he’s burning a cross. The Third World Alliance is not pleased. There is an investigation. There is a dark hallway ass-kicking. Duff refuses to shower for three weeks in lieu of filing a written complaint. He calls it a Worker’s Action. He says Eugene V. Debs did not wear Ban roll-on. Nikki’s friends start calling Duff names like “Smelldolf Hitler” and “Smell Gibson” and “Smells Like Teen Suicide.”

But not to his face.

When he finally reunites with soap, there’s talk of a duo.

They pull six songs together, try to think of a name.

Nikki likes Pure Candy.

Duff likes the Four Tercels.

Pure Tercel plays two shows, the second in the basement of a basement, where Duff meets a girl called Agnes. She has a tattoo of a shotgun wound and a birthmark shaped like the Amalfi Coast. Agnes takes Duff by the hand, wants to show him something out back before the next set.

They disappear for the winter.

That spring Nikki graduates with a degree in pulling the graveyard shift at a motel beneath an exit ramp. There’s an actual bell on the counter that dings. Once in a while they get a frugal tourist, otherwise it’s mainly battered moms and pregnant runaways, plus a guy named Winslow who buys a large black drip and a dozen donuts every morning, sits with his feet dangling over the empty pool. Winslow chuckles, takes a bite, says he’s “Killing Myself Fatly with This Song” when anyone asks, which no one does, so he tells whoever walks by, which just makes them walk faster.

There’s a cassette deck by the cash box. Nikki plays John Coltrane all shift long, thinks “Alabama” is the saddest melody he’s ever heard, plays it over and over louder and louder until dawn, the more trebly and dissonant the better.

Each note a shard of inalterable beauty.

Each note like bug spray for the insane.

THE FAMILY IN 227 never comes back. Nikki gets sent over with gloves and a mop. There’s trash everywhere — socks, empties, a bear with all the stuffing hugged out of its neck.

Leaned up against the mini fridge is an old acoustic.

Covered with finger grime and Dead stickers.

It screams hippie chicks with thrift skirts and anklets. It begs for braless fatties to kick off their sandals and spin in the wet grass.

“Anything good?” the manager asks.

“Nope,” Nikki says, then rumbles through half a dozen Neil Young in front of the campus Quiznos twice a week. There is a hat. The professor with the too-neat beard drops a twenty and winks. The kind of girls who hang out and listen hang out and listen. The kind of girls who smoke sigh and kill off another Marlboro red.

On a random Tuesday Duff is there, at the edge of the crowd.

Nodding along, or pretending to.

They get beers.

“Where’s Agnes?”

“Let the door hit her where the good lord split her.”

“She dump you?”

He grins, down a tooth or two. “Yeah, pretty much.”

There are some hugs.

Within a week Duff starts a band with a dude named King Ink. They need a bass player. Duff says, “No sweat, I’ll vouch for your candy ass.”

King Ink calls at midnight, asks Nikki does he want to join.

“You got a name yet?”

“Scrofula,” King Ink says.

There’s a long pause.

“It’s a disease with glandular swellings. Most likely a cousin of tuberculosis.”

There’s a long pause.

“Listen, you in or not?”

“You haven’t heard me play.”

“Duff is an astute judge of character.”

“That,” Nikki says, “is without question the least true thing anyone has ever said aloud.”

King Ink insists Scrofula will be the Guns N’ Roses of the greater Ohio Valley area. By the second practice it’s clear they will never be the Guns N’ Roses of the greater Ohio Valley area. King Ink is six-foot-six, wears velvet boots, and has the goatee Rosemary’s baby would have grown his freshman year at Sarah Lawrence. Duff says not to worry, the dude is a genius. Besides, once they buy a sampler they’ll be playing thousand-seat venues.

Scrofula does six shows, opens two nights for Particle Bored.

And blows them off the stage.

Duff says there’s strong label interest. Smoking Goat out of Chicago. Reeves Rimini wants to produce. Duff says King Ink says everyone needs to put up three hundred to cut a demo. Scrofula rehearses the shit out of their setlist, hones it to a tight forty minutes with a killer payoff, a tune Nikki wrote called “Those Che

lsea Mournings.” After practice they crack beers, load all the gear into the van for the trip to the studio. King Ink takes them each by the shoulders, insists they’re on the verge of something.

“Special? No, big. Big? No, huge.”

Nikki gets chills down his arms. King Ink orders three large pies to celebrate, splurges on extra pepperoni, takes the van to go pick them up.

And never comes back.

NIKKI DOESN’T TOUCH a guitar for a year, then one day spots a ’73 Tele Thinline hanging in a pawnshop, and can’t buy it fast enough. The thing so clean it sings. So dirty it’s a slut. It takes months to learn that Chet Atkins lick, let alone the James Burton. He writes a dozen new songs, thinks about maybe being frontman for once, get some kids just want to learn their parts, keep their mouths shut.

Memorial Day comes and Nikki agrees to a weekend roadie with day shift clerks he barely knows. Robot, Marcellus, and Gay Don. They camp out one night, hit a titty bar the next, on the way back stop in Columbus to piss. It’s hot. Nikki’s Replacements T is wet to the shoulder blades. They’re at the edge of a campus, a football powerhouse. A strip of dives ten blocks long, beer-soaked carpet and specials in every window, JAEGER TUESDAYS!

“Let’s drink,” Gay Don says.

“It’s not Tuesday,” Nikki says.

“Good point,” Robot says. “Let’s find a museum instead.”

“I only have eight bucks,” Nikki says.

“Which you should immediately spend on ointment for your vagina,” Marcellus says.

By the fourth place they’re shit faced.

Gay Don starts telling everyone who’ll listen they’re a band, mostly because Nikki brought the Thinline in its ratty swing-jazz case, not wanting to leave it in Robot’s Camry, which doesn’t lock. Gay Don says they’re playing the Attic at midnight. A couple girls are like Oh, really? not putting much in it. The bartender rolls his eyes, cuts limes. Someone checks the paper. Turns out there really is an Attic, a tiny dump across the river, but it’s closed tonight.

“Unannounced show,” Marcellus says, swears they’ll leave tickets at will call for anyone who buys a round. A few people actually do. Robot runs down the set list for them, how they rock Bon Jovi covers and Robert Johnson covers and John Cage covers. How they crush Black Sabbath covers and Black Flag covers and Black Uhuru covers. Nikki figures as the guitar player his gig is to hang back and be silent and cool and superior, one foot up on the rail. It’s worthy of some sort of paper, sociology or physics, how easily the rest fall into unspoken roles. Marcellus lead vocals and acne scars. Robot drums, tatted neck to wrist. Gay Don on eyeliner and bass.

Welcome Thieves

Welcome Thieves