- Home

- Beaudoin, Sean

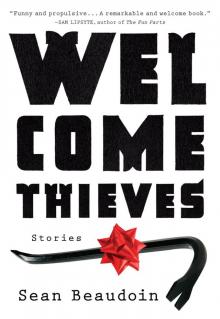

Welcome Thieves Page 2

Welcome Thieves Read online

Page 2

None of them plays an instrument as far as Nikki can tell.

In some ways it’s better than actually being in a band.

From bar to bar the story is honed, more believable, less believable. Robot and Gay Don spin the Japanese tour, groupie orgies, failed label deals. People move closer, buy fresh rounds. Nikki concludes that a lie stumbled upon is infinitely more believable than a lie presented. That being a fool allows others to reveal themselves. That the power of belief is redemptive and carries a special allure for the perpetually bored.

On the other hand, it’s pretty clear they’re being dicks. It’s a question of how many drinks are required not to acknowledge it.

“We don’t get backup singers on our rider soon, it’s time for a new manager,” Robot tells an underage girl who claims to sing.

“Bullshit,” says a dyed waitress, two sticks of gum and a tray digging into her hip. “Tell me the name of this supergroup again?”

Gay Don looks at Nikki, mouths, Oh fuck.

It’s worthy of an entirely different paper, this one on the mathematics of sheer dumbassedness, the fact that it hasn’t come up yet.

“Yeah, man, what is your name?” says the big dude in a Tupac shirt who bought the last round. Doubt flares. Conversations stop. There are maybe twenty people in the bar, a group of sports guys with backward caps and team sweatshirts, a few townies and metal dudes wristing foosball. Nikki can feel an undertow, an ugly gravity, an inevitable beat down coming. For some reason the entire room turns to him as he leans on the guitar case with half a glass of someone else’s beer.

“We are Crustimony Proseedcake.”

It’s the first thing that pops into his head. The Tao of Pooh had been on the nightstand of the last girl he hooked up with, a yoga teacher who shot a killer game of nine ball. He’d read a few pages while she was in the shower.

There’s a lengthy silence.

Sun blares under the half-door, causes the rubber floor mats to steam.

And then Robot smashes a bottle on his forehead, yells, “Pro-fucking-seed-cake!’ ”

Solved.

Out come the vodka shots. Out come the backslaps and air jamming. Every ten minutes someone new walks in and the entire bar yells, “Pro-seed-cake!”

Crustimony hits two more spots, adds groupies and acolytes and believers and skeptics and marketing majors and homeless artists and lab assistants and lacrosse team wingers by the block. It’s late afternoon. Everyone is very drunk. Nikki has just been in the bathroom with a girl who had horrible breath and after a minute said, No no no, my breath, and pushed him away, stumbling back to where her friends sat on a broken Ping-Pong table.

The music pounds and people dance and then it’s time to leave, everyone promising to come see them that night.

“Sound check at ten sharp, y’all,” Robot says, one last salute at the door.

All the way back to the car they laugh, barely able to stand. It’s a running guy hug, a shoulder-squeezing, unbalanced affair. They punch and slap and checklist through the afternoon’s triumphs.

“How did you come up with the Attic?” Marcellus asks.

“Fuck if I know,” Gay Don says.

“And can you believe this character?” Robot says, arm around Nikki. “Pro-seed-cake? That was, seriously, a stroke of genius.”

Marcellus agrees. “You pick something one iota less weird and we were gonna get stomped.”

“First rule of performance art,” Gay Don says. “It can never be bullshitty enough.”

“I dunno,” Nikki says. “You can only fuck with people so long, you know?”

“Wrong,” Robot says. “You can fuck with them forever.”

They get back in the Camry and drive home.

DUFF CALLS FROM REHAB, apologizes. His teeth practically gleam over the phone. Huge surprise, he met a guy in group, a drummer who played with the Ainsley Lord Experience. Who played with Screaming Jim Slim. Duff and the drummer lift together three days a week, cardio on Saturdays. Trust exercises. Buy each other shots of wheatgrass, carry tractor tires up hills. Duff says they’re starting a new thing, “Super commercial, but hip, you know?”

“Not really.”

Duff says that Nikki has to move to Brooklyn. Has to bring his killer bass tone. “The plan is to slay New York first, then hit Japan, and eventually own all of music itself.”

There are whiffs of steps 4 through 7. There is the unmistakable resonance of true belief.

Tara listens to Nikki’s half of the conversation, rolls her eyes. Tara leans over his back, says, No way. Tara says, Thanks for nada. Tara says, Don’t let him do this to you again.

Nikki says thanks for nada.

“Wait, for real?” Duff says, preclick.

“I’m so proud of you,” Tara says, pulls Nikki onto the bed. Later they go to Blockbuster and rent Juno, split a bottle of cabernet, open a second one but leave it on the counter.

Eight months later Nikki sees Duff windmilling power chords next to Paul Shaffer, getting the band nod from Letterman.

Give it up, ladies and gentlemen, for the Torrentials!

NIKKI CALLS A LAWYER, who laughs. Thirty days later he wakes up thirty.

Three decades old.

Might as well be ten.

He hits the occasional open mic, doesn’t mind playing for beer, likes the feeling of a 90-watt spot on his face while a half-drunk softball team talks through the changes.

His best song is called “Rime of the Ancient Silas Marner.”

No one laughs.

There is some disappointment.

But no regrets, because he’s never going to be as good as the tool from the Strokes, let alone Charlie Parker, so why keep pretending?

Tara says he never wants to do anything fun.

Tara says he’s getting fat.

Tara splits after a long talk conducted on two sleeping bags zippered together.

She takes the Cabriolet, leaves Rose.

Nikki holds out as long as he can, another couple winters, finally pawns the Thinline for next to nothing. Sells his amps and speakers and heads and pedals and straps and cords and tuners for even less. He donates the sax to an elementary school. All that’s left is the acoustic, which he plays for his three-year-old daughter, who loves to dampen the buzzing strings with her tiny palm.

Rose especially digs Sly’s “Family Affair,” doesn’t seem to mind that Nikki always fucks up the changes to “Good-bye Mr. Porkpie Hat.”

“Daddy?”

“Yes?”

“Daddy?”

“Yes?”

Rose likes to start a question but never knows how to finish. For a second Nikki thinks that’s a pretty good metaphor for every string he’s ever plucked, every melody he’s never written.

But then decides that’s just more arty bullshit.

“Daddy?”

“Yes?”

Her little mouth trembles, desperate to force out something of value. Nikki can already tell by the time she’s thirteen she’ll cut her hair at an angle across her jaw, dye the tips purple, get a nose ring. She’ll have posters of bands that don’t exist yet above her bed and a leather-pant boyfriend. She’ll crash a car and burn down a bodega and spend freshman year teaching herself to play Siouxsie on the trombone.

She’s got the time, she’s got the genes.

She’s got the jones.

Nikki tries not to be jealous, fails.

“C’mere little petal,” he says, plays Rose another song.

The Rescues

1995 Ford TraumaHawk SL Ambulance

The Dayton State Cornholers. Actually Musketeers, but still. They really only took Danny because of his willingness to hit. And be hit. His high school had made an unlikely run at the state lacrosse championship and it was more or less concluded his coarse and speeding bulk was the reason. There was a scholarship offer. He was thinking enlist. Strap on the Kevlar, get seriously ballistic. Also, he hated to study.

&n

bsp; But the old man told him to smarten up.

“Have fun in Ohio. Try not to be a pussy.”

By the second day Danny had a reputation. Bigger players stepped out of the way as he came tearing across the field, pads slapping, bent low for maximum collision.

“Chillax, brohman,” they said, mimed doobie fingers. “It’s only practice.”

“Chillax this,” he said, hit even harder.

There was a purity to mayhem. To split lips and sprung hamstrings, when mud tasted as good as blood. Coach started calling Danny “Junkyard.” Girls stared in the caf. He became a minor god of chaos and cracked ribs, the terrifying silence of a blindside tackle or unattended erection. Danny’s teammates jumped at the bite of his voice, soaked in the wisdom of his elbows, Saturday nights with pitchers of Bud and gathered blondes hazed with smoke and stories, Then Junkyard flies over and absolutely destroys the dude! I bet he still hasn’t gotten up!

He took every dare. Eat a worm, run through traffic naked, follow that hulking waitress into a stall and make like a two-backed animal, moan loud enough for the entire bar to hear, release untold tiny flagellates across her skirt more than a little on purpose, leave proof of the negation of life itself.

Release being just another form of destruction.

Or, hey, maybe that’s thinking too much. Fucking’s fine but lacrosse is decisive. Put the ball in the net, tally it up. Put your man on his ass. Constantly. Assert a hominid dominance. Not out on the street after six tequilas and a trip to the drunk tank: within a grid and according to strict and unwavering rules. Because to face a rival in pads whose chest is made for nothing so much as to be stepped on, and then to do so, is a work of art that not only resists the censure of those who absorb no pain, who form opinions on the sidelines, but often results in the ability to sit in a packed bar all night long without a dollar in your pocket and howl for pitcher after pitcher of cheap beer utterly secure in the knowledge that someone will eventually bring it.

Junk-yard! Junk-yard! Junk-yard!

The third game of the season Danny took a cheap shot in the crease, bled out like a pig. Time was called. His teammates kicked at the dirt and swore revenge, without the sac to actually follow through. So he sat for forty-eight stitches with a fish hook and no anesthetic, sprinted from the locker room and doled near-Balkan retribution. The Cornholers won by eleven. Even Coach was like, “Bring it down a notch, Danny, they’re gripping their pearls.” And it was true, the other team full of guys with something better on the side, prelaw, premed, all of them suddenly asking, Who needs this madness?

Danny did.

Every second, minute, inch, foot.

Sweat and uniform and pads and stick.

The Cornholers rose in the standings, playoffs in sight for the first time in decades. Then the last game of the season a big-name Ivy League team rolled in, none of their players much except the midfielder, all jaw and shaved head. A towering Cossack with three-day stubble and yellow breath. His eyes were empty, lips flecked with blood.

“I’ve heard of you,” the Cossack said.

“No you haven’t.”

“I’ve seen you play.”

“No you didn’t.”

They danced and hacked and elbowed all the way across the field.

It hurt.

Danny watched as the Cossack clotheslined their forwards, dished cheap shots to the fullbacks, delivered pain with pro efficiency. With a radiant grin. There was no hesitation, no nuance. It was almost like being in the backyard with Dad again, running drills, pushing limits. Exploring the fine line between Just Doing It and puking a streak of Gatorade across the neighbor’s fence.

“You and me? We could be friends,” the Cossack whispered, as they chopped and muscled in front of goal. “Let’s hang out, go to dinner and a show.”

Danny knew he had to quip back. Be funny and casual. Arch and bold. But his shit talk was gone. The Clint stare, the Bruce smirk. He wanted to take off his spikes, feel his toes in the grass. He wanted to eat graham crackers dunked in milk, go home and lie under a quilt, watch something old and dumb like Melrose Place, the episode where Heather Locklear wears tight pants.

During timeouts the guys punched Danny’s arm and shouted encouragements, confused by the loss of their beautiful madman.

Smack him! Shut his mouth, Junk!

Even coach wadded an entire pack of Dentyne.

Christ on a stick, Danny, you waiting for an invite?

In the third quarter he stole a pass and raced up the left sideline. A breakaway. Just the net and thirty open yards. The goalie waited, resigned. They both knew Danny was going to score and then pretend like he couldn’t control his momentum, feed the dude sixty pounds of marinated shoulder.

There was no sound, no sweat, no grass.

Just his feet, just his breath.

And then the Cossack coming.

Fast and from behind.

A low giggle, the heavy tromp of cleat.

They connected with a slobber-crack that echoed across the field, rose through the stands, halted the game.

An hour later Danny woke in the ambulance while a nurse with a Kid ’n Play lid hooked him to a tube. It felt like he was wearing himself sideways.

“Did we win?”

“I doubt it.”

“There a problem?”

The nurse slipped Danny her phone number. “After the surgery? You decide you don’t need them leftover Oxys, you give me a call.”

That night the entire squad gathered around the bed, stared at his leg in traction, the pins in his hip, said all the things you say, relieved when the orderly finally kicked them out.

The article in the campus paper was intentionally vague, combed by a paralegal for liability.

A week went by, then three, then six.

Six teammates visited, then three, then none.

Some pimply kid cleaned out Danny’s locker, dropped off his gear jammed into two Ninja Turtles pillowcases. He was allowed to stay enrolled, but no more scholarship. “The good news is you can concentrate on your classes,” a counselor of some sort suggested. Friends stared at their onion rings while Danny limped through the caf. He’d pass the team on the quad, all the chillaxers and brohmen lowering their eyes, his torn gait evidence of something damning.

Maybe even contagious.

Transformation was, according to a textbook he’d partially read, inevitable.

The walker became crutches became a cane.

He dropped out, put on weight.

“Oh, wow,” people said in the produce aisle, at the movies. “You still in town?”

Danny found the ambulance chick’s number, called her up. The next day he got a job delivering pizza, put a deposit on an apartment off campus, right above a comic book shop. The owner tended to frown while he limped though the stacks, showed off his scars, winked at nerdy girls, lifted a few Green Lanterns.

Is the Fist of Power lost forever?!!? the covers asked. Will a monarch emerge from within the Demon Chrysalis?!!?

1983 Plymouth Scamp “Pizza Monster” Delivery Truck

It was nearly midnight on a rush order, window down, radio blaring. The classics. Verse, chorus, verse. Buh-buh-buh Bennie and the Jets. The DJ complained about the heat. The stink of pepperoni rose from the floorboards. Zeppelin was next, with their grunts and squeals, their Middle Earth routine. It was like, if the dude was such a Druid, why was he trying so hard to sound black?

Danny spotted a glint of chrome on the side of the road, locked ’em up. In a clearing stood an ultimate Frisbee squad, coed, mud-flecked, ponytails and orange slices. Their van steamed, hood propped with a Wiffle bat. He wanted to give them all a hug for thinking that ironic things had actual meaning, their discounted sneakers and sailor tattoos and patchy facial hair.

“Y’all need some help?”

They cheered.

He eased out of the cab, limped across the double yellows.

The cheering stopped.

/> “Holy shit,” someone said.

Danny tended to forget he was him. Broken. Looming. Might as well rock a leather apron and a chainsaw.

A girl in hot pants stepped forward, aimed something shiny and black.

“Shoot,” he said.

Her lighter illuminated the engine, a knot of rust and ticking heat. Danny leaned over and pretended to tighten a hose, spelled out his name in crankcase grease.

“Okay, fire it up.”

Hot Pants slid behind the wheel and jammed in the key. The van magically roared to life, air thick with ozone and the tang of high fives.

“Oh, fuck it,” Hot Pants said, and jumped into Danny’s arms.

Everyone laughed. Beers were retrieved from the cooler, the radio cranked. Bros danced with bros, whitely and without shame. Danny stood in the middle of it all, drinking in just the sort of love that can only come from an ultimate Frisbee team on the side of the road in the cricket-heavy dark.

2009 Black Acura “Sport Package” ZDX

By August he was resurrecting two cars a week. Sorority girls and math department heads. Adjuncts and transfers. The occasional rumpled provost. It was a small college town, dark country roads, way too easy to get stuck or stranded.

Word got back to Pizza Monster.

Mikey Atta spun dough on his middle finger, dared Danny to charge fifty a car. Hippie Tim buttoned his tweed jacket, said it was a lawsuit on a platter. Gail, sweaty-pink and nearly poured into her waitress uniform, said everyone had one important skill in life and Danny’s was to rescue people.

“You’re an automotive Saint Bernard.”

Mikey Atta leaned through the pass and air-wristed a blow job. The busboys fell out in hysterics. A woman looking at the menu frowned, took her son by the elbow, let the screen door slam.

Welcome Thieves

Welcome Thieves