- Home

- Beaudoin, Sean

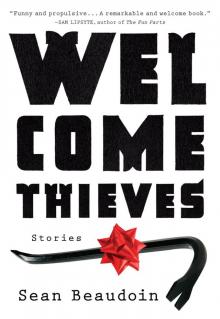

Welcome Thieves Page 3

Welcome Thieves Read online

Page 3

“So what’s your one important skill?” Danny asked.

“Folding napkins,” Gail said, finishing another pile. She had short bangs and cat eye glasses, spoke out of the corner of her mouth in a sardonic way that waitresses with advanced degrees now living off campus with a guy named Zach sometimes tended to. It was no secret that Danny wanted to spend entire shifts carnally entwined, locked in the walk-in while Gail’s hot breath and cries for mercy defrosted several flats of ricotta. It was also no secret to her boyfriend, Zach, who didn’t like it a bit, but got one look at Danny’s enormous shaved head and swollen knuckles and decided to be evolved about the whole thing.

“You got something for me?” she whispered.

Danny took the cash and slipped a baggie into her apron pocket.

“Incoming!” Hippie Tim yelled. It was his one important skill: radar. Ten seconds later a booth’s worth of sorority girls gaggled in, ordered a round of side salads, and then went to town on free breadsticks.

Mikey Atta flicked his tongue between two fingers.

Tom Petty oozed from the juke.

Danny stood out on the deck, where a black Acura circled the lot, laid a patch all the way down the street.

“Delivery up!” Hippie Tim yelled, sliding round glasses back up his nose. “You think you can you handle this one, Danny, or should I call in the National Guard?”

1969 Porsche 911T

Bob Devine had been ordering an X-large with sausage and peppers three nights a week since his wife emptied the closets and took the twins to her mother’s in Corfu. She left a note peanut-buttered to the wall letting Professor Devine know where he could stick his teaching assistant, a fey Asian kid with Elvis sideburns. Three months later Elvis transferred to Duke, leaving behind a suitcase full of uncorrected papers and a formal harassment complaint now working its way through dual ethics panels. The only thing the professor got to keep was the mortgage and an ancient Porsche up on blocks, extradition hopeless, the twins destined to hit puberty under the cruel Ionian sun.

He opened the door before Danny could even knock. Boxers, chest hair, silk robe. They’d had one class, History of Some Shit or Another. Danny was still on scholarship then. Cocky and entitled. Pawing at girls. Never did the reading, never knew the answers. Shiloh. Yalta. Teapot Dome.

Professor Devine lifted the lid, grabbed a slice, shoved it deep.

“Is America wonderful or what?”

“As long as you’re American.”

“Well, all empires have their flaws. But few have unlimited toppings.”

“Or unlimited credit.”

Devine added two quarters to the bill, unaware that SHITTY TIPPER blinked on the screen every time he ordered. Gail, whose one important skill was actually coding Linux, set the system up. SHITTY TIPPER was license for Mikey Atta to loogie the mozz, to crimp the professor’s dough with a grease-black sneaker print before ladling sauce. At first Danny was against it, but was now fairly sure it made no difference. Every single thing in every single restaurant in the world has been on the floor at least once.

“Hey, you wouldn’t happen to have any extra napkins, would you?”

“How many you need?”

Professor Devine held up sixty dollars.

Danny took it, palmed over a baggie.

“Don’t eat the whole thing at once.”

Professor Devine smiled.

“I have no idea how you ever failed my class.”

1993 Nissan Pulsar NX

A mile down the road a car was pulled over, hazards on. A girl stood embossed in brake light. Tall, Persian, smirking. Born to ruin teachers and preachers, mock family values on yards of thigh alone. Or maybe just really pretty.

“Need a hand?”

“Nice hat.”

Danny turned the purple cap around. Nothing to be done about the rest of the uniform, khakis and a polo shirt. Even the truck was purple, a graphic of Frankenstein on the hood going, “Grrr . . . Me no skimp on toppings!”

He rolled out jumper cables, tried not to limp.

“Hey, I recognize you.”

“Texas Chainsaw? That was someone else.”

The girl laughed. “No, I used to come to games. Up in the bleachers, a bunch of us with a jug of wine.”

“Cheering away?”

“Depended on the score.”

Danny clamped the batteries together, as always expecting a sudden jolt to fuse his teeth. Instead, the Nissan roared to life. Flowers swayed in the halogens. The radio kicked in, a dissonant trombone blaring out of speakers more expensive than the rest of the car put together.

“Who’s this?”

She cranked the knob, drowning out frogs and grasshoppers nestled in the weeds.

“Sun Ra.”

They faced each other, covered with sweat. Haze hung like a wet sheet above the oily grass and between the oaks.

“What’s your name?”

“Steak.”

Danny knew it was a test. If he made a dumb joke, like medium rare or well done or free range, she’d immediately cross him off the list, the same method she’d erased four years’ worth of frat boys with.

“Hey, Steak?”

“What?”

“Wanna go out sometime?”

She smiled, hair impossibly long and Nile black, swung it out of her face like a flag of victory. “We’re already out.”

Danny watched as she folded herself back into the car, spun the wheel, fishtailed away.

2004 Volkswagen Vanagon

He found her in an old student directory. Stalled for an hour then dialed. No answer. Redialed. Voicemail. Danny left a message while Hippie Tim wrote him up for making calls on company time. In the kitchen, Mikey Atta snapped a towel at the ass of the busboy who wore a turban. A girl at the counter who’d been gazing at the menu like it was the New Testament finally asked if the Spinach Goddess came with extra spinach.

“Cold pies getting colder!” Hippie Tim yelled, rang the bell.

Danny gunned it across town. First a raft of sausage subs to the bio lab, along with two baggies of Vicodin. Then a departmental meeting, twelve wilted salads and a smaller baggie for the security guard, a dude named Heavy Kev, who let Danny in even on nights it was obvious he was fronting an empty box.

On the way back his phone buzzed.

Steak, Steak, Steak.

“Danny?” a secretary said. “Hold for your father.”

Fuck, fuck, fuck.

“You there?”

“Sort of.”

“Any news about the team?”

“No.”

“What about coaching?”

“What about it?”

“My office has a few open slots. You buy a tie, I could place you.”

“I already have a job.”

“Bussing crusts?”

“There’s profit in humility.”

“Christ, even your voice is fat. You sound like I should send you a bra.”

“Actually, what you should send me is three thousand dollars.”

His father slipped out of permanent hard-on mode.

“Are you serious?”

Danny was.

The ambulance chick who wrapped his knee, name of Miss Kay, bought his entire script of Oxy after all. He’d decided to tough it out, ignore the pain. Needed the cash. When those were gone, they met for a beer, talked through shopping doctors, what to say, how to beg without begging. Danny came up with a few flourishes, thought with some practice he might even bust out tears on command. She nodded. “Big dude with a cringe? Puppy eyes like you got? Shit, I’d write you for three refills myself.”

When the clinic finally cut him off, a male nurse with a nose ring sent out front to say next time it was the cops on speed dial, Miss Kay offered Danny a job.

“On the ambulance?”

“No, in the saddle.”

“Wait, what?”

“Pill donkey. You apply somewhere does take-out. Thai, Chinese, whatever. Keep you

r tips, make special deliveries for me on the side.”

Hippie Tim hired Danny the next day.

Within a month he started to skim. Shorted baggies, palmed aspirin for Oxy, pocketed the difference. It was really dumb. Like Miss Kay was never gonna find out. Like numerous painfully unhigh adjuncts wouldn’t demand refunds. Like whole dorms full of underopiated sophomores would fail to vow revenge.

“Dad, I’m in real trouble here.”

“You spent three large on a girl?”

“No, a tattoo.”

“You gotta be shitting me.”

Danny wasn’t. It was pure old-school, Yakuza-style, from thigh to clavicle, carp and koi and an intricate blood-red moon slung over rows of Japanese waves. Twenty-six hours of table time already, on his stomach, an orgy of pain as an ancient woman with a bamboo stick jabbed ribbons of black and orange beneath his every surface and delicate layer.

“Give Mom a kiss,” Danny said, hanging up as a black Acura pulled from the 7-Eleven with a screech. Windshield smoked, chrome grill, shiny and mean. It cut off four cars and got right on his bumper.

Danny switched lanes.

The Acura switched lanes.

He switched again.

The Acura switched again.

Dad rang, went to voicemail.

Delivery texts poured in. Hippie Tim.

RUSH ORDER.

PEPPERONI.

DICK HEAD.

Danny played it cool, smoothed across campus like, hey, no problem, and then at the six-way stop by the bowling alley punched it way late through a red. There was a chorus of horns as he swept under the entrance to the state park. The little truck howled, blew by picnic tables and families and statues of founding Whigs, a purple blur through the high rolling switchbacks until he was absolutely sure there was nothing behind him except an old couple in a Vanagon taking pictures through their windshield.

1961 Ford Fairlane Taxi

“Where to?”

Danny repeated the address, chewing his tongue to ribbons. For some reason he’d dry-swallowed four Adderall from the case Miss Kay bought off a guy named Taco she met at Pilates. The pills jumped all over him right away, a thousand cups of coffee with a 120-volt chaser. His head felt light and untethered, like it might just float up out the window and through the atmosphere, begin taking cloud samples.

“You sure this is the place?” the driver asked, idling in front of vaguely Soviet concrete apartments. A pack of kids taunted each other crunching gravel circles on their ten-speeds. They gave Danny the finger, whirled off down the street.

“Yeah, this is it.”

Steak opened the door wearing a faded dress, straight from the Kansas Tornado collection, barefoot, beautiful.

Also, all her hair was gone.

Every inch, head gleaming, scalp shorn white. Her eyes dared Danny to be shocked, another test.

“Something’s different,” he said. “New perfume?”

She smiled and walked into the kitchen.

“You hungry?”

He wasn’t. Jangly-high, zero appetite.

“Starving.”

They chopped side by side, boiled water, made sauce from scratch, those goofy little cans of tomato paste that seem to contain nothing at all. When the penne was ready Danny rinsed it, a couple going over the edge. They lay in the sink, pale and soft, abandoned.

“We lost a few good men today.”

Steak laughed.

“Want to hear a story?”

“Sure.”

It was about this meathead campus hero, let’s call him Donny, and the feats of madness and stupidity she personally witnessed him perform back in the day. Like the time Donny rode a bike in the library naked, or the time he spray-painted JESUS SAVES SOULS AND RECLAIMS THEM FOR VALUABLE CASH PRIZES across the face of the student union, or the time he put an M-80 in a bucket of ranch dressing in the caf. How funny it all was. How tough and raw and compelling he had been. How, despite the fratishness and cult of moronicism it seemed to engender — just the sort of thing she normally despised — how inexplicably hot Donny had made her.

“Yeah, whatever happened to that guy?”

She got up and walked into the bedroom, kicked dirty towels into a closet. He lined up Adderall like a parade, crushed their dreams with the back of a spoon. They banged rails, compounds breaking down, binding together, a slurry of toxic waste seeping into all the appropriate organs.

“This is good. This is just what I needed,” she said, a trickle of blood from one nostril.

“This is bad. This is not what you need,” he said, wiping it away.

Steak pulled off her dress. Her breasts lolled in opposite directions.

“Jesus.”

“Hera,” she said, knelt and began to lick the tissue around his ruined knee, trace the raw crossing lines. The scars rose, a livid white and then pink, her fingernails following the waves of his tattoo, around the sun and sky and schools of hungry koi.

For an album side they worked their way across the length and width of her futon. It was sensory immersion, action without thought, armpit and convexity and gentle undulation. There was no goal, nothing to attain. At intervals throughout the night she got up for smokes or to change the music. Danny got up to soap his stinking neck and fish out another baggie. Dawn came. They sweated through noon, drank more wine, ordered food. She licked his asshole. He bit her thigh. It was dinner and then midnight and then in a granular, panting lull they listened to Mingus, which Danny knew because Steak said “This is Charles Mingus.” The music was a carnival orchestra, like being jabbed with a fork. It whirled and beeped and honked with glee. In the center of the bedlam was Charlie, who held it all together, plucked away at his bass, sang and hummed and drove the other musicians like sled dogs across the tundra. At any other time Danny would likely have hated this prophet, this Charles Mingus. He would have snapped the dial, searched for ZZ Top or “Separate Ways,” but now, lying across Steak, he understood. Genius was a code pulsed down from a binary star, a revelatory percussive wave. It was math plus rhythm, an equation of intervals, the sound and then not the sound, something that could never be snorted or faked or even approached by the fastest, most devastating sprint across an open, grassy field.

HE WOKE FROM a dream about transmission schematics. Mostly for German sports cars of various makes and vintages, but mainly the 1957 DKW Monza, when Steak kicked the mattress.

She was showered, head powdered, wearing a clean dress.

“It’s Monday.”

“So?”

She gave him a glass of ice water and stroked his forehead, on the verge of confiding something. Even from the depths of his hangover, the cracked porcelain of his brainpan, Danny knew it was too soon for a declaration of love.

But he was wrong.

Steak told him that she was truly, deeply in love.

With her girlfriend.

The one out of town on a roofing job.

Who was coming home.

Soon.

He rolled over and the room rolled with him. “A make-popcorn-while-watching-lawyer-shows-in-pajamas-together kind of girlfriend?”

“No.”

The girlfriend’s name was Lula. Lula worked as a carpenter. Lula had broad shoulders and thick, callused hands that felt like loving bark on Steak’s soft and spoken-for hips.

Also, she was very sorry.

Steak confessed to being empathic, which would make for a bad cable television series but was still a rare and inexplicable gift. She explained that Danny was one of those people with a strain of need running so deeply through their core that she had no defense against it. Steak said this sort of person, him, sometimes barged into her life and ruined everything stable she’d worked so hard to build. She said Danny was a destroyer. A barbarian at the gate. Both emotionally and sexually. Physically and mentally. And right this moment, on an early Monday morning, she had briefly managed to wrest back control.

“So

, can you please leave? Like, now?”

He stood, naked, covered in the patchy sheen of their commingling. The bodily proof of forty-eight hours of a deep and genuine connection.

“You’re shitting me, right?”

Steak scratched her calf with the other foot, balanced on one leg like the rare tidal bird she was. If the look on her face signaled anything, it was pure dismay.

And possibly the desire for fresh shellfish.

That Car Again

Danny got to Pizza Monster four hours late, the lot mostly empty.

Except for a mean-looking black Acura, all rims and grill.

His stash was in the walk-in. His cash was in his locker.

For a second Danny considered turning around and driving the truck west, keep going until he ran out of gas or maps.

A guy with a bulge in his waistband sat at the counter. He had huge hands and a nylon jacket and looked like an extra from a movie about swindling the London mob. Danny was scared, but probably not as much as he should be. If the life of a student was one long bong hit leavened with intermittent study, the life of an adult was the acknowledgment that there was only one rule: Everyone gets what they deserve.

Gail was talking to Hippie Tim by the salad bar. Mikey Atta’s forearms shed flour as he snapped a rolled-up towel at the ass of the busboy with the strawberry birthmark. Danny slid next to Miss Kay in the upholstered corner booth.

Her Afro stood straight up, like a silo. She wore blue eye shadow, pretty like a Jackie O blazer: trim, immaculate, lost to another era.

“You’re late.”

“Yeah.”

“Bossman says you’re a shitty worker.”

“Hard to argue there.”

“How’s the knee?”

“Gone. Thrashed.”

Miss Kay tapped salt on her wrist and licked it.

“So in terms of problems that matter, you got my money?”

“No.”

“You got my drugs?”

“Mostly no.”

The big guy at the counter swung around. Danny turned over a fork, readied the tines.

“Look, I know I messed up, but is this necessary?”

“Come again?”

The guy yanked at the bulge in his waistband. Gail walked over to the register. He aimed his wallet, paid, left a nice tip. A station wagon with a bunch of screaming kids idled into the lot. The guy got in the passenger seat and kissed the woman driving. They looked both ways before pulling back into traffic.

Welcome Thieves

Welcome Thieves